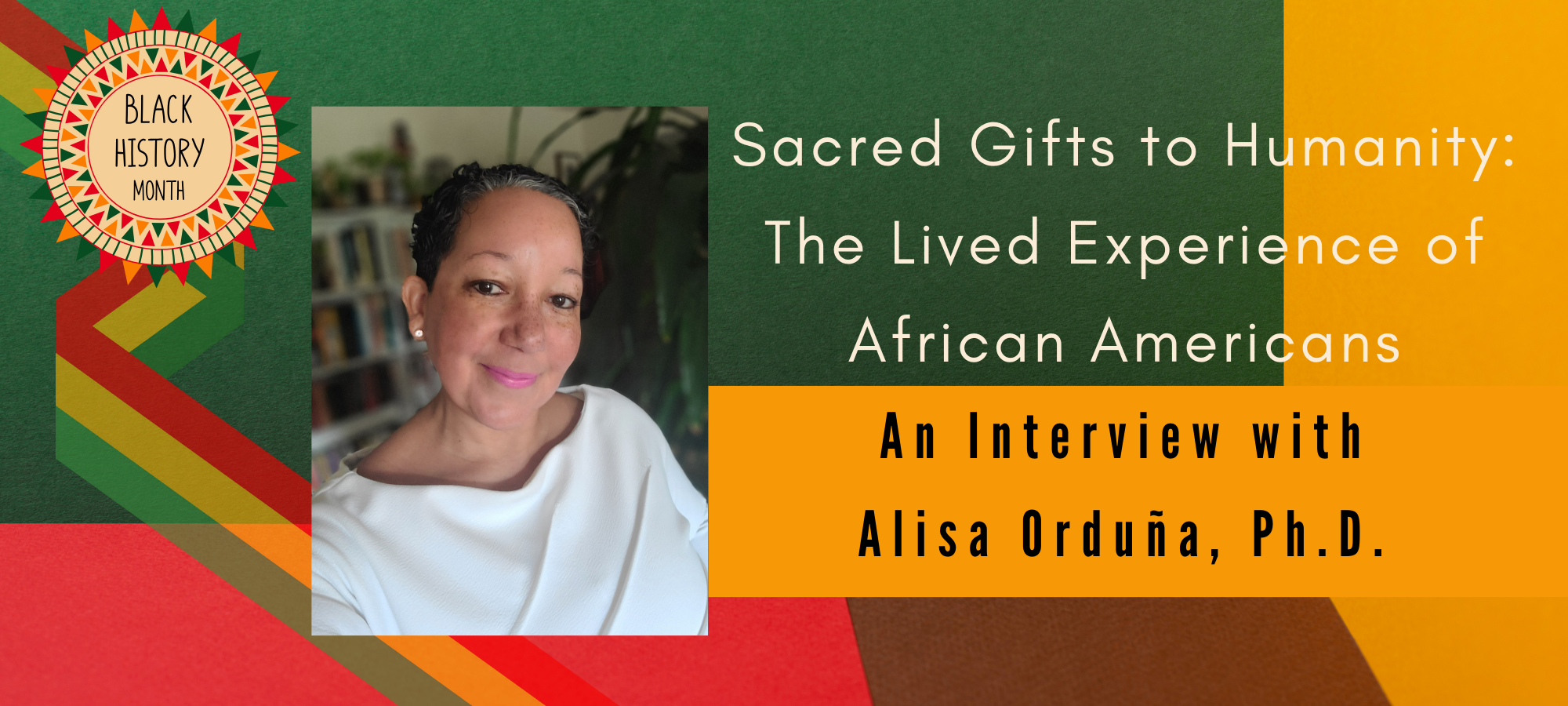

An Interview with Alisa Orduña, Ph.D.

Alisa is a graduate of Pacifica’s specialization in Community, Liberation, Indigenous, and Eco-Psychology. She has been a practitioner, policy analyst, collaborator and thought leader in the urban community development field for the past 25 years. I’m delighted to speak with her.

Angela: You wrote your dissertation at Pacifica on “Òṣun Consciousness: Unearthing Anti-Black Biases in the Los Angeles Homeless System Soul as reflected in the Sacred Histories of the African American Experience.” One of the things I value about Pacifica and our scholars is the beauty and depth of thought that goes into understanding even the worst of human behavior. And in studying anti-Black bias in the homeless system, you have undoubtedly witnessed attitudes and behaviors that are, for lack of a better word, ugly. Yet the language and ideas of your dissertation, which gives a soul to the system and ascribes sacredness to the African American experience, are inherently beautiful. That which has a soul can be healed, or at least understood, it seems to suggest. Was that your intention or am I reading too much into a title?

Alisa: Far too often in the arenas of public policy and human services systems, we approach through a false narrative of objectivity as if systems do not have souls, intentions, cultures, and other elements of the human experiences. As if systems are not amplified mechanical designs, but are human-designed pathways that select who and who is not eligible to access the needed resources to thrive within society. So I wanted to humanize as a way of heightening areas of accountability by calling attention to the “soul” of the homelessness response system and opening up space for emergence and transformative change. In other words, humans design and implement systems, so there is nothing stopping us from modifying them to mitigate intentional or unintentional harm to certain system navigators. Yes, even a broken, lost, or numbed soul can be healed.

Alisa: Far too often in the arenas of public policy and human services systems, we approach through a false narrative of objectivity as if systems do not have souls, intentions, cultures, and other elements of the human experiences. As if systems are not amplified mechanical designs, but are human-designed pathways that select who and who is not eligible to access the needed resources to thrive within society. So I wanted to humanize as a way of heightening areas of accountability by calling attention to the “soul” of the homelessness response system and opening up space for emergence and transformative change. In other words, humans design and implement systems, so there is nothing stopping us from modifying them to mitigate intentional or unintentional harm to certain system navigators. Yes, even a broken, lost, or numbed soul can be healed.

Angela: The phrase “sacred histories of the African American experience” has a remarkable power to it. How can we find the sacred in an experience that began for many with ancestors in the early seventeenth century experiencing the trauma of enslavement? Do you find a connection with that original trauma and the number of African Americans today who are currently homeless, or is that too simplistic an idea?

Alisa: As an African American, I have noticed that too often we are taught our history in dominant spaces such as school, cultural media platforms (films, documentaries, news stories…), and other ways we communicate culture in our society, through narratives that lead with slavery and trauma. It is as if our cultural identity is linear and did not begin until we arrived to Turtle Island on the Trans-Atlantic Slavery cargo ships. Even in modern times, especially in the human/social services sectors, negative stereotypes are reified by harmful data that prioritizes deficits over our resilience and assets, not to mention neglect in holding the very visible hand of oppression and White supremacy accountable. Through my work, I have come to listen-in to stories of lived experiences as sacred gifts to humanity and given the ability to hold onto emotions and experiences such as love, joy, sorrow, grief—against a culture that leans to dehumanization, it was important to uplift the (hi)stories of the African American experience within the realm of sacredness. I also believe our re-membering of who we are outside of the White gaze through forms of knowledge passed on through our foods, medicines, stories, dreams, dance, music, song, prayers—is how we have been able to continue moving through projected acts that cause trauma within our lives.

I do think there is a connection to anti-Black biases/prejudice that were developed in the American psyche to justify the kidnapping and enslavement of African people with the number of Black people experiencing homelessness today. At so many inflection points in our history when we could have moved toward a more integrated and diverse society, we have chosen segregation through law, policy, and violence (e.g., Jim Crow, Plessy vs. Ferguson, anti-Affirmative Action bills). In my research, the compilation of police surveillance of Black and Brown communities in public and private spaces; continued practices of redlining or use of zoning to enforce racial segregation that isolate Black folks in communities with high pollution, little city services, away from jobs, etc.; forced displacement through urban renewal, eminent domain, and gentrification; racialization of mental health services, began to feel like a strategic attack on Black beingness. Instead of creating cultural approaches to help people access systems of care, Black people are disproportionally criminalized for being poor, being a renter, living with a mental illness or substance use addiction, being a single mother/father, etc. with stringent measures of social control, as if we are still ascribed to an imaginary plantation and the act of Emancipation never happened. So it is not the act of slavery by itself, more the psychological justification that was generated to numb enslavers to the brutal act of such structural violence.

Angela: The study of the psyche has been around for thousands of years, and every culture has had its own wisdom and ways in approaching it. But the modern field of psychology, as we know it, has its origins with the work of scholars like Jung, Freud, etc. It has led to a stereotype of the psychologist as a Caucasian man, perhaps smoking a pipe, contemplating a female patient lying on a couch. How do you envision the future of depth psychology evolving from this, and how is Pacifica’s CLIE program part of that vision?

Alisa: It is so important that we expand the written narrative about the influences of our founders as a starting point. For instance, Freud is said to have studied ancient Egyptian culture, and we know that Jung spent some time visiting a few countries in Eastern Africa, as well as American Indian communities and Black communities here in the States. It is important to note that no one cultural group owns or even knows the vast mysteries of the mind, and thus, we must be open to understanding the layers of self and which ones have developed through socialization, which are primordial, which are shared elements across cultural groups that mark our belonging as humans. I am grateful to Pacifica’s CLIE program. I am not sure I would have pursued my Ph.D. anywhere else. It was important for me to learn the classics, AND, have space to explore the emergence of my own voice (or rather the voice wanting to speak through me). I am often in awe when I see the synopsis of upcoming Pacifica dissertation defenses, as each is its own medicine to help fill some fracture in our world wrought by this period of colonialism and its hunger for domination. I truly believe we are at a critical juncture and collectively preparing to pivot to a new age of consciousness, and I think Pacifica in general and the CLIE program in particular, have the skill set to manage ambiguity, unknowingness, and change, and our students, staff, faculty, and alumni will be called upon in increasing ways. I see the impact on my own work and think it is no coincidence that I brought my dissertation topic to the world during the pandemic and immediate aftermath of the George Floyd racial reckoning.

See Part II of this interview to read more.

Dr. Alisa is a writer and lover of the literary arts, in addition to her work in homelessness policy. She is the author of Oshun’s Calabash, Dancing Across Cuba into the Memory of the Embodied African Soul & Finding Home and Unearthing the Feminine. She is a contributing author to Seeing in the Dark: Wisdom Works by Black Women in Depth-Psychology.

Alisa is a Los Angeles native and enjoys spending time reading, in nature, or being present for her nephews.

Angela Borda is a writer for Pacifica Graduate Institute, as well as the editor of the Santa Barbara Literary Journal. Her work has been published in Food & Home, Peregrine, Hurricanes & Swan Songs, Delirium Corridor, Still Arts Quarterly, Danse Macabre, and is forthcoming in The Tertiary Lodger and Running Wild Anthology of Stories, Vol. 5.